|

IDENTITY CARDS

Frequently Asked Questions

PRIVACY INTERNATIONAL

August 24 1996

This report provides an analysis of the key aspects of identity (ID) cards and related technologies. It has been prepared by Privacy International in the wake of widespread concern across the world about the implications of modern ID systems. Our intention here is to discuss the evidence at an international level and to promote debate about the claims made about such card systems.

The principle author of this report is Simon Davies, Director General of Privacy International and Visiting Fellow in the London School of Economics. Assistance and input to this report was provided by members of PI throughout North America, Europe and Asia.

CONTENTS

1. How many countries use ID cards ?

Identity (ID) cards are in use, in one form or another in numerous countries around the world. The type of card, its function, and its integrity vary enormously. Around a hundred countries have official, compulsory, national IDs that are used for a variety of purposes. Many developed countries, however, do not have such a card. Amongst these are the United States, Canada, New Zealand, Australia, Ireland, the Nordic countries and Sweden. Those that do have such a card include Germany, France, Belgium, Greece, Luxembourg, Portugal and Spain.

The use of sectoral (specific purpose) cards for health or social security is widespread, and most countries that do not have a national universal card, have a health or social security card (in Australia, the Medicare Card, in the United States, the Social Security number), or traditional paper documents of identity. The reverse is also true. In Sweden, while there exists a ubiquitous national number, there is no single official identity card.

Generally speaking, particularly in advanced societies, the key element of the card is its number. The number is used as an administrative mechanism for a variety of purposes. In many countries the number is used as a general reference to link the card holders activities in many areas.

An analysis of identity cards around the world reveals a number of interesting patterns. The most significant of these is that virtually no common law country has a card. Nor does the economic or political development of a country necessarily determine whether it has a card. Neither Mexico nor Bangladesh have an ID card. And, until this year, India had no card (even now, the card, strictly speaking, is a voter registration card rather than a national ID card). Generally speaking, however, the vast majority of developing countries have either an ID card system or a document system,often based on regional rather than national authorization.

In many countries, identification documents are being replaced by plastic cards, which are seen as more durable and harder to forge. Card technology companies are well organized to conduct effective promotion of their product, and companies have moved into the remotest regions of the world. Many Asian and African nations are replacing old documents with magnetic stripe or bar coded cards. The South African Passbook is being replaced by a card. The UK drivers license is also being replaced by a photo ID card from 1996. The change from one form of ID to another is invariably accompanied by a change to the nature and content of data on the document.

2. What are the main purposes of ID cards?

ID cards are established for a variety of reasons. Race, politics and religion were often at the heart of older ID systems. The threat of insurgents or political extremists, and the exercise of religious discrimination have been all too common as motivation for the establishment of ID systems which would force enemies of the State into registration, or make them vulnerable in the open without proper documents. In Pakistan, the cards are used to enforce a quota system, In China, they are used as a tool of social engineering.

In the United Kingdom, current proposals for a national ID card are fuelled by the need to develop a document which is acceptable to other European countries, as well as a belief that the scheme might help fight crime. In Australia, the purpose of the proposed card was to fight tax evasion, and, in New Zealand, to establish Social Welfare entitlement. The Dutch card has the dual purpose of helping to improve government administrative efficiency, while playing a key role in dismantling border controls.

At the heart of such plans is a parallel increase in police powers. Even in democratic nations, police retain the right to demand ID on pain of detention.

In recent years, ID cards have been linked to national registration systems, which in turn form the basis of government administration. In such systems - for example Spain, Portugal, Thailand and Singapore - the ID card becomes merely one visible component of a much larger system. With the advent of magnetic stripes and microprocessor technology, these cards can also become an interface for receipt of government services. Thus the cards become a fusion of a service technology, and a means of identification.

This dual function is expressed well by one Philippines Senator in the introduction to her 1991 ID card Bill as an integrated relationship between the citizen and his government.

3. What are the main types of ID systems in use?

Broadly expressed, there are three different forms of ID card systems :

1. Stand Alone documents

2. Registration systems

3. integrated systems

Stand Alone ID documents are issued in primitive conditions, or in environments which are subject to sudden economic or political change. Often, areas under military rule or emergency law will issue on the spot ID cards which are, essentially, internal passports. Their principle purpose is to establish that a person is authorized to live in a region.

The majority of ID systems have a support register which contains parallel information to that on the card. This register is often maintained by a regional or municipal authority. In a minority of countries, this is a national system. Even countries such as France and Germany have no national ID card register. Germany has constitutional limitations on the establishment of any national number.

Virtually all card systems established in the past ten years are Integrated systems. They have been designed to form the basis of general government administration. The card number is, in effect, a national registration number used as a common identifier for many government agencies.

It is interesting to note that residents of countries which have ID documents or papers, often refer to these in the English as ICs or Identity cards. The Afghan Tazkira is a 16 page booklet, but is often referred to as a card. Likewise, in Poland, where the form of ID is a passport-like booklet called 'Dowod osobisty' (or, literally, personal evidence it is translated universally as a card.

4. What information do the cards contain?

The majority of cards in use in developed nations have the holders name, sex, date of birth, and issuing coordinates printed on the card itself. An expiry date, and number is also embossed, along with a space for a signature. A minority of sectoral cards include a photograph. Official cards issued by police or Interior Ministries generally do include a photograph, and in many cases, a fingerprint.

In Brazil, for example, all residents are obliged to carry at all times a plasticated flexible card the size of a credit card bearing a photograph, thumb print, full name and parents' names, national status (Brazilian national or alien resident) and a serial number.

In Chile, it is a small plastic card with photograph, names, date and place of birth, signature, and personal number. The Korean 'National Registration Card' shows name, birth date, permanent address, current address, military record, issuing agency, issued date, photograph, national identification number, and prints of both thumbs. The Malaysian identity Card has the date of birth, parents name, religion, ethnicity, sex, physical characteristics, place of birth and any other identification mark on the reverse side. The front face carries the photograph, fingerprints, and IC number.

The Pakistan card carries a large amount of data, including photograph, signature, card serial number, government official's signature, Date of issue, DRO/Post office number, ID Card number, name, father's name, Temporary Address, Permanent Address, identification marks, and date of birth

The German "Personalausweis". is a plastic ID card which contains, on the front side, name, date and place of birth, nationality, date of expiration, signature and photo. The name, date of birth and number of the card are machine readable (ocr). On the back side are address, height, color of eyes, issuing authority and date of issue. Addresses are changed by putting a sticker on the old address.

The Italians have a larger format card (three by four inches) containing Identity number, name, photo, signature, fingerprint, date and place of birth, citizenship, residency, address, marital status, profession, and physical characteristics

In a small number of cases, notably Singapore and some Asian nations, cards contain a bar code, which is seen by authorities as more reliable and durable than a mag stripe. The French are also moving toward a machine readable card.

5. What is the financial cost of an ID card system?

In the Philippines, the United Kingdom and Australia, the cost of implementing an ID system has been at the forefront of political and public opposition to nationwide schemes. The Philippines proposal relied on government estimates that were drawn, as is often the case, from estimates calculated by computer industry consultants. These were found to under-estimate the true cost by eight billion pesos over seven years. The proposal lapsed because of this factor.

In Australia, the cost of the proposed ID card failed to take into account such factors as training costs, administrative supervision, staff turnover, holiday and sick leave, compliance costs, and overseas issue of cards.. Other costs that are seldom factored into the final figure (as was the case in Australia( are the cost of fraud, an underestimate of the cost of issuing and maintaining cards, and the cost to the private sector. As a consequence, the official figure for the Australia card almost doubled between 1986 and 1987.

Private sector costs for complying with an ID card are very high. The Australian Bankers Association estimated that the system would cost their members over one hundred million dollars over ten years. Total private sector compliance costs were estimated at around one billion dollars annually.

The official figure for the Australia card was $820 million over seven years. The revised estimate including private sector and compliance costs, together with other factors, would amount to several times this figure.

The UK Governments CCTA (Information Technology Center) advised that a national smart ID card would cost between five and eight pounds sterling per head but this figure does not include administration, compliance etc. When he announced the introduction of a national ID card in August 1996, the Home Secretary, Michael Howard, advised that the cost as likely to be at least double the CCTA estimate (ten to fifteen pounds).

6. Can ID cards assist law enforcement?

Although Law and Order is a key motivation for the establishment of ID cards in numerous countries, their usefulness to police has been marginal. In the UK. Home Secretary Michael Howard told the 1994 Tory Party conference that he believed an ID card could provide an invaluable tool in the fight against crime. This claim was toned down somewhat during the gestation of the proposal.

Howard's claim received little support or substantive backing by academic or law enforcement bodies. The Association of Chief Police Officers (ACPO) said that while it is in favor of a voluntary system, its members would be reluctant to administer a compulsory card that might erode relations with the public. Dutch police authorities were not generally in favor of similar proposals in that country, for much the same reason. 9

According to police in both countries, the major problem in combating crime is not lack of identification procedures, but difficulties in the gathering of evidence and the pursuit of a prosecution. Indeed, few police or criminologists have been able to advance any evidence whatever that the existence of a card would actually reduce the incidence of crime, or the success of prosecution. In a 1993 report, ACPO suggested that street crime, burglaries and crimes by bogus officials could be diminished through the use of an ID card, though this conflicted with its position that the card should be voluntary.

In reality, only a national DNA database (such as has just been opened in Britain) or a biometric database (such as is being proposed in Ontario) might assist the police in linking crimes to perpetrators.

Support along these lines for the introduction of cards is also predicated on the assumption that they will establish a means of improving public order by making people aware that they are being in some way observed. Sometimes, cards are proposed as a means of reducing the opportunity of crime. In 1989, the UK government moved to introduce machine readable ID cards to combat problems of violence and hooliganism at football grounds. The general idea was that cards would authorize the bearer to enter certain grounds and certain locations, but not others. They could also be canceled if the bearer was involved in any trouble at a ground or related area. The idea was scrapped after a report by the Lord Chief Justice claimed that such a scheme could increase the danger of disorder and loss of life in the event of a catastrophe at a ground.

One unintended repercussion of ID card systems is that they can entrench widescale criminal false identity. By providing a one stop form of identity, criminals can easily use cards in several identities. Even the highest integrity bank cards are available as blanks in such countries as Singapore for several pounds. Within two months of the new Commonwealth Bank high security hologram cards being issued in Australia, near perfect forgeries were already in circulation.

This conundrum has been debated in Australia, the UK and the Netherlands. It relies on the simple logic that the higher an ID cards value, the more it will be used. The more an ID card is used, the greater the value placed on it, and consequently, the higher is its value to criminal elements.

There appears to be a powerful retributive thread running along the law and order argument. Some people are frustrated by what they see as the failure of the justice system to deal with offenders, and the ID card is seen, at the very least, as having an irritant value.

7. What impact do ID cards have on tax evasion and welfare fraud?

The need to develop measures to combat fraud have prompted the introduction of widescale, integrated, information technology in most developed countries. These strategies have sometimes involved the use of cards.

The cost of fraud can be significant, but the causes are often rooted deeply in human and organizational issues that technology may not be entirely capable of solving.

Benefits agencies around the world have identified key precursors to fraud. Three levels of fraud are often expressed, in order of significance, as:

False declaration, or non declaration, of income and assets (problems which are also components of non-declaration of income for tax)

Criminal acquisition of multiple benefits using false identification

More conventional fraud and theft of benefit payments

These conditions should be considered alongside numerous other factors which contribute to benefit overpayment, including clerical error and genuine misunderstanding about the terms of payment.

One of the central problems in responding to the question of fraud has been the general difficulty in assessing its nature and magnitude. Virtually no ethnographic research exists, and the data that do exist are drawn principally from internal and external audits, management reviews, and retrospective studies. Many methodologies have the effect of assessing risk, rather than quantifying actual fraud. No standard guidelines have yet been developed to assess the sort of information technology used in fraud control and identification. Additional problems are found with the definition of fraud, and the terms of audit, which often do not parallel the parameters of internal departmental cost/benefit analyses.

Estimates of the extent of fraud on benefits agencies varies widely. The Toronto Social Services Department, for example, officially estimates fraud by way of false identity at less than one tenth of one percent of benefits paid, whereas the Australian Department of Social Security estimates the figure at ten times that amount. Estimates of fraud vary widely between one tenth on one per cent of total benefits, to as high as four percent. Britain's popular estimate of one to two billion pounds is, in international terms, at the high end of the spectrum.

The Parliamentary Select Committee on the Australia Card warned that the revenue promises of the card scheme were little better than "Qualitative assessment" - in other words, guesswork. The Department of Finance refused to support the Health Insurance Commission's (HIC) cost benefit estimates (the HIC was the principle agency behind the scheme). Revenue was constantly revised downward, while the costs continued to rise. The Department of Social Security insisted that the ID card would have done little or nothing to diminish welfare fraud. In evidence to the parliamentary committee investigating the proposal, the Department said that much less than one per cent of benefit overpayments resulted from false identity. The Department decided that it would pursue other means of tackling fraud. The DSS in the UK argued against ID cards on the same grounds.

The Australian DSS estimates that benefit overpayment by way of false identity accounts for 0.6 per cent of overpayments, whereas non-reporting of income variation accounts for 61 per cent. The key area of interest, from the perspective of benefit agencies, lies in creating a single numbering system which would be used as a basis for employment eligibility, and which would reduce the size of the black market economy.

8. Can ID cards help to control illegal immigration?

Yes and no. Although the immigration issue is a principle motivation behind ID card proposals in continental Europe, the United States and some smaller developing nations, the impact of cards on illegal immigration has been patchy

The abolition of internal borders has become a primary concern of the new European Union. The development of the Schengen agreement between the Benelux countries, France, Spain and Germany calls for the dismantling of all border checks, in return for a strengthening of internal procedures for vetting of the population. France and the Netherlands have already passed legislation allowing for identity checks on a much broader basis, and other countries are likely to follow.

The establishment of personal identity in the new borderless Europe is a contentious issue, but is one which appears (to many people) to be a broadly acceptable trade-off for the convenience of greater freedom of movement within the union.

The use of a card for purposes of checking resident status depends on the police and other officials being given very broad powers to check identity. More important from the perspective of civil rights, its success will depend on the exercise of one of two processes : either a vastly increased level of constant checking of the entire population, or, a discriminatory checking procedure which will target minorities.

The two arguments most often put forward to justify the quest to catch illegal immigrants in any country are (1) that these people are taking jobs that should belong to citizens and permanent residents, and (2) that these people are often illegally collecting unemployment and other government benefits.

The image of the illegal immigrant living off the welfare of the State is a powerful one, and it is used to maximum effect by proponents of ID cards. When, however, the evidence is weighed scientifically, it does not bear any resemblance to the claim. When the Joint Parliamentary Committee on the Australia Card considered the issue, it found that the real extent of illegal immigrants collecting government benefits was extremely low. The report described a mass data matching episode to determine the exact number. Of more than 57,000 overstayers in New South Wales, only 22 were found in the match against Social Security files to be receiving government unemployment benefits. That is, 22 out of a state population of five million. The Department of Immigration and Ethnic Affairs (DIEA) had earlier claimed that the figure was thirty times this amount (12.4 per cent as opposed to 0.4 per cent of overstayers).

Indeed most immigration authorities worldwide base their estimates on qualitative assessment. Again quoting from the Australia Card inquiry It became clear that the estimates for illegal immigrants were based on guesswork, the percentage of illegal immigrants who worked was based on guesswork, the percentage of visitors who worked illegally came from a Departmental report that was based on guesswork....The Committee has little difficulty in rejecting DIEA evidence as being grossly exaggerated.

9. Do ID cards facilitate an increase in police powers ?

Generally speaking, yes. A Privacy International survey of ID cards found claims of police abuse by way of the cards in virtually all countries. Most involved people being arbitrarily detained after failure to produce their card. Others involved beatings of juveniles or minorities. There were even instances of wholesale discrimination on the basis of data set out on the cards.

While it is true that cards containing non-sensitive data are less likely to be used against the individual, cards are often alleged to be the vehicle for discriminatory practices. Police who are given powers to demand ID invariably have consequent powers to detain people who do not have the card, or who cannot prove their identity. Even in such advanced countries as Germany, the power to hold such people for up to 24 hours is enshrined in law. The question of who is targeted for ID checks is left largely to the discretion of police.

The wartime ID card used in the UK outlived the war, and found its way into general use until the early 1950s. Police became used to the idea of routinely demanding the card, until in 1953 the High Court ruled that the practice was unlawful. In a landmark ruling that led to the repealing of the National Registration Act, and the abandonment of the ID card, the Lord Chief Justice remarked :

... although the police may have powers, it does not follow that they should exercise them on all occasions...it is obvious that the police now, as a matter of routine, demand the production of national registration identity cards whenever they stop or interrogate a motorist for any cause....This Act was passed for security purposes and not for the purposes for which, apparently it is now sought to be used.... in this country we have always prided ourselves on the good feeling that exists between the police and the public, and such action tends to make the public resentful of the acts of police and inclines them to obstruct them rather than assist them. 16

10. Do ID cards facilitate discrimination?

Yes. The success of ID cards as a means of fighting crime or illegal immigration will depend on a discriminatory checking procedure which will target minorities.

The irony of the ID card option is that it invites discrimination by definition. Discriminatory practices are an inherent part of the function of an ID card. Without this discrimination, police would be required to conduct random checks, which in turn, would be politically unacceptable.

All discrimination is based on one of two conditions : situational or sectoral. Situational discrimination targets people in unusual circumstances. i.e. walking at night, visiting certain areas, attending certain functions or activities, or behaving in an abnormal fashion. Sectoral discrimination targets people having certain characteristics i.e. blacks, youths, skinheads, motor cycle riders or the homeless. ID cards containing religious or ethnic information make it possible to carry this discrimination a step further.

Several developed nations have been accused of conducting discriminatory practices using ID cards. The Government of Japan recently came under fire from the United Nations Human Rights Committee for this practice. The Committee had expressed concern that Japan had passed a law requiring that foreign residents must carry identification cards at all times. The 18-member panel examined human rights issues in Japan in accordance with the 1966 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Japan ratified the covenant in 1979. The Alien Registration Law, ``the Committee complained in its report, is not consistent with the covenant''.

Ironically, the Parliaments of several European nations, including France and Holland, have accepted a law introducing the obligation to identify oneself in numerous situations including, for instance, at work, at football stadiums, on public transport an in banks. While the card is voluntary in name, it is in effect a compulsory instrument that will be carried at all times by Dutch citizens. Moreover, foreigners can always be asked to identify themselves to authorities at any moment and in any circumstance.

French police have been accused of overzealous use of the ID card against blacks, and particularly against Algerians. Greek authorities have been accused of using data on religious affiliation on its national card to discriminate against people who are not Greek Orthodox.

11. To what extent will an ID card become an internal passport?

An ID card, by definition, is a form of internal passport. Virtually all ID cards worldwide develop a broader usage over time, than was originally envisioned for them. This development of new and unintended purposes is becoming known as function creep.

All ID cards - whether voluntary or compulsory - develop into an internal passport of sorts. Without care, the card becomes an icon. Its use is enforced through mindless regulation or policy, disregarding other means of identification, and in the process causing significant problems for those who are without the card. The card becomes more important than the individual.

The use of cards in most countries has become universal. All government benefits, dealings with financial institutions, securing employment or rental accommodation, renting cars or equipment and obtaining documents requires the card. It is also used in myriad small ways, such as entry to official buildings (where security will invariably confiscate and hold the card).

Ironically, many card subjects come to interpret this state of affairs in a contra view (the card helps streamline my dealings with authority, rather than the card is my license to deal with authorities). The Australia Card campaign referred to the card as a license to live.

It is clear that any official ID system will ultimately extend into more and more functions. Any claim that an official card is voluntary should not imply that a card will be any less of an internal passport than would a compulsory card. Indeed a voluntary card may suffer the shortcoming of limited protections in law.

During the campaign against the Australia Card, talk back radio hosts had become fond of quoting a paragraph of an HIC planning document on the Australia Card:

It will be important to minimize any adverse public reaction to implementation of the system. One possibility would be to use a staged approach for implementation, whereby only less sensitive data are held in the system initially with the facility to input additional data at a later stage when public acceptance may be forthcoming more readily.

The campaign organizers stressed the pseudo-voluntary nature of the card. Whilst it was not technically compulsory for a person to actually obtain a card, it would have been extremely difficult to live in society without it.

12. What happens if an ID card is lost or stolen?

Virtually all countries with ID cards report that their loss or damage causes immense problems. Up to five per cent of cards are lost, stolen or damaged each year, and the result can be denial of service ad benefits, and - in the broadest sense - loss of identity.

There exists a paradox in the replacement of cards. The replacement of a high security, high integrity card involves significant administrative involvement. Documents must be presented in person to an official. Cards must be processed centrally. This process can take some weeks. However, a low value card can be replaced in a lesser time, but its loss poses security threats because of the risk of fraud and misuse.

People who lose a wallet full of cards quickly understand the misfortune and inconvenience that can result. A single ID card when lost or stolen can have precisely the same impact in a persons life.

13. What are the privacy implications of an ID card?

In short, the implications are profound. The existence of a persons life story in a hundred unrelated databases is one important condition that protects privacy. The bringing together of these separate information centers creates a major privacy vulnerability. Any multi-purpose national ID card has this effect.

Some privacy advocates in the UK argue against ID cards on the basis of evidence from various security threat models in use throughout the private sector. In these models, it is generally assumed that at any one time, one per cent of staff will be willing to sell or trade confidential information for personal gain. In many European countries, up to one per cent of bank staff are dismissed each year, often because of theft.

The evidence for this potential corruption is compelling. Recent inquiries in Australia, Canada and the United States indicate that widespread abuse of computerized information is occurring. Corruption amongst information users inside and outside the government in New South Wales had become endemic and epidemic. Virtually all instances of privacy violation related to computer records.

Data Protection law is wholly inadequate to deal with the use of ID cards. Indeed legislation in most countries facilitates the use of ID cards, while doing little or nothing to limit the spectrum of its uses or the accumulation of data on the card or its related systems.

14. Has any country rejected proposals for ID cards?

Yes, several. France's ID card, for example, was stalled for many years because of public and political opposition. Until the late 1970s, French residents were required to possess a national identity document. This was made of paper, and was subject to the risk of forgery. In 1979, however, the Ministry of the Interior announced plans for a higher integrity automated card encased in plastic. The card was to be used for anti terrorism and law enforcement purposes. The card, to be issued to all 50 million residents of France, was to be phased in over a ten year period. New laser technology was to be used to produce the cards.

At first, there appeared to be little resistance to the proposal, but in a fashion similar to Australian experience (see below), political and public resistance grew as details of the plan emerged. Although no identity numbers were to be used (only card numbers) there was some concern over the possible impact of such cards. Frances information watchdog, CNIL, managed to suppress the machine readable function of the proposed cards, though optical scanning made magnetic stripes somewhat redundant. Publications such as Le Figaro expressed concern that the cards and related information could be linked with other police and administrative systems.

Public debate intensified in 1980, with the Union of Magistrates expressing concern that an ID card had the potential of limiting the right of free movement. In response to these and other criticisms, the ruling of CNIL was that no number relating to an individual could be used, but that each card would carry a number. If the card had to be replaced, a new number would apply to that particular document.

In 1981, the Socialists were elected, and the fate of the ID card was reversed. In an election statement on informatics, Francois Mitterrand expressed the view that the creation of computerized identity cards contains a real danger for the liberty of individuals. His concern was echoed by the minister for the Justice, Robert Badinter, explained that ID cards presented a real danger to the individual liberties and private life of citizens, and the new Minister for Interior then announced the demise of ID cards in France. The plan was re-introduced under a later conservative government.

In the United States, issues of individual autonomy and national sovereignty appear to have dominated the Identity card issue. Despite a high level of anxiety over fraud, tax evasion and illegal immigrants, successive administrations have refused to propose an ID card. Extension of the Social Security Number to the status of an ID card has been rejected in 1971 by the Social Security Administration task force on the SSN. In 1973 the Health, Education and Welfare (HEW) Secretary's Advisory Committee on Automated Personal Data Systems concluded that a national identifier was not desirable. In 1976 the Federal Advisory Committee on false Identification rejected the idea of a national identifier. In 1977 the Carter administration reiterated that the SSN was not to become a national identifier, and in 1981 the Reagan Administration stated that it was explicitly opposed to the creation of an ID card. Throughout the debates over health care reform, the Clinton Administration has also constantly stressed that it is opposed to a national identifier.

It remains the case that the SSN continues to be a de facto national identifier, despite constant rulings and legislation to the contrary. With an estimated four to ten million false or redundant numbers, there is concern that the SSN might in fact help to entrench illegal immigration or fraud, nevertheless, there is no plan to upgrade the number.

Some of the federal agencies mandated to use the SSN are the Social Security Administration, Civil Service Commission, Internal Revenue Service, Department of Defence, food stamp program, Department of Justice, Department of energy, Department of Treasury, Department of State, Department of Interior, Department of Labor, Department of Veterans Affairs, and to all federal agencies for use as an identifier for record keeping purposes. State agencies can also use the number for welfare, health and revenue purposes, and third parties are mandated to request the SSN for verification for products or services.

In recent months, proposals by the Clinton administration to reform the US health sector have involved plans to streamline the administration and information flow amongst all health insurers and providers. This proposal involves a national card system, though the federal administration has insisted that the card would not be general in nature. A recent scheme for employment verification also provoked an outcry when concerns were raised that it would lead to the creation of a national ID scheme.

The most celebrated campaign against a national ID card occurred a decade ago in Australia. In 1986, the Australian Government introduced legislation for a national ID card called the Australia Card. Its purpose was to form the basis of the administration of major government agencies, to link the finance and government sector, and to perform the standard identification functions necessary in the commercial and Social Security sectors.

The card became the focus of the single biggest civil campaign in recent Australian history, and certainly the most notable campaign of its type anywhere in the world. Tens of thousands of people took to the streets, and the government was dangerously split over the issue. The proposal caused such hostility that the card was abandoned in 1987.

In 1991, the government of New Zealand drew up a strategy to reform its health care and social welfare system through the development of a data matching program, and the introduction of a sectoral national identity card. The card would link major Government departments and would have the capacity to track all financial dealings and even geographical movements. The plan was known as "social bank", and the card was to be known as a Kiwi Card.

The proposal for a national card had angered civil libertarians and law reform groups, partly because the card would be used to enforce a part payment health system, partly because it was to be established without protections in law, and partly because it would create significant problems for certain minority groups. Under the leadership of the Auckland Council for Civil Liberties, a campaign of opposition was formed in August 1991. Unlike the Australian campaigners four years earlier, the New Zealand campaigners had a precedent from which to develop a strategy.

Although the fight to destroy the Kiwi Card was not anywhere near as spectacular as the Australia Card campaign, the controversy resulted in the abandonment of the card, and the adoption of a low integrity entitlement card (issued in two forms) for the purpose of health benefits.

Smart Card Evolution

The REAL ID Act: Why Real ID Cards Should Be Based on Smart Card Technology

This paper provides support for the use of smart card technology to implement state driver’s licenses issued to comply with the requirements of the REAL ID Act of 2005, which was passed to improve the security of state-issued driver’s licenses and personal identification cards.

By: Smart Card Alliance

Background

In the United States, driver’s licenses are issued by individual states. States also issue identification cards for use by non-drivers. States set the rules for what data is on a license or card and what documents must be provided to obtain a license or card. States also maintain databases of licensed drivers and cardholders.

The REAL ID Act of 2005 stipulates that after May 11, 2008, “a Federal agency may not accept, for any official purpose, a driver’s license or identification card issued by a State to any person unless the State is meeting the requirements” specified in the REAL ID Act.

The Act includes the following requirements:

- A driver’s license or identification card must include certain specific information and features.

- A driver’s license or identification card cannot be issued unless certain specific documentation is presented.

- The state must verify all documentation presented with an application.

- Driver’s licenses or identification cards issued to persons who are present in the United States only temporarily can be valid only for the amount of time for which the persons are authorized to be in the United States.

- Controls and processes must be established to ensure the security of the issuance process.

- Each state must maintain a motor vehicle database and provide all other states with electronic access to the database.

The REAL ID Act also stipulates that the technology incorporated into the driver’s license or identification card must meet the following requirements:

- It must support physical security features designed to prevent tampering, counterfeiting, or duplication of the credential for fraudulent purposes.

- It must be a common, machine-readable technology, with defined minimum data elements.

The Department of Homeland Security has the authority to issue regulations and set standards for compliance with the REAL ID Act.

Smart Card Technology and Identity Applications

Smart card technology is currently recognized as the most appropriate technology for identity applications that must meet certain critical security requirements, including:

- Authenticating the bearer of an identity credential when used in conjunction with personal identification numbers (PINs) or biometric technologies

- Protecting privacy

- Increasing the security of an identity credential

- Implementing identity management controls

The following active Federal government programs currently use smart card technology:

- The Federal employee and contractor Personal Identity Verification (PIV) card

- The new United States ePassport

- The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Registered Traveler program

- The DHS Transportation Workers Identification Credential (TWIC) program

- The DHS First Responders Access Credential (FRAC) pilot program implemented in the National Capitol region

Countries around the world (such as Germany, France, Malaysia, and Hong Kong) use smart cards for secure identity, payment, and healthcare applications. In addition, public corporations (including Microsoft, Sun Microsystems, Chevron, and Boeing) use smart employee ID cards to secure access to physical facilities and computer systems and networks.

In response to Homeland Security Presidential Directive-12, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) has published the Federal Information Processing Standard 201 (FIPS 201), providing specifications for an interoperable Federal PIV card. The standard calls for a combined contact/contactless smart card that can authenticate the cardholder for both physical and logical access. The FIPS 201 standard not only applies to Federal employee and contractor IDs; it is also being used to specify the underlying requirements for the TWIC, Registered Traveler and FRAC credentials.

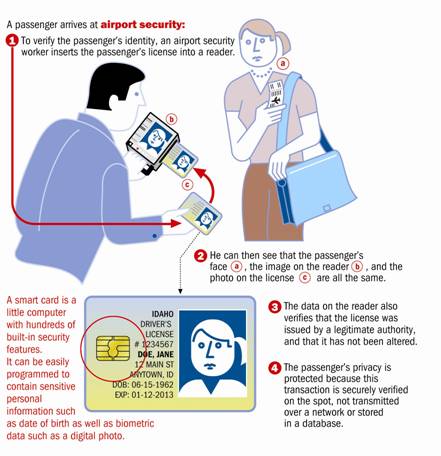

States could incorporate the same proven PIV card technology into a state-issued Real ID (i.e., a driver’s license or identification card issued to comply with the REAL ID Act). The PIV-based Real ID could then be used to authenticate the bearer in a “federal” situation, such as checking in at an airport (Figure 1). This Real ID card could also incorporate biometric factors (such as a facial image or fingerprint template) to help verify the cardholder’s identity.

Figure 1: Using a Smart-Card-Based Real ID for Airport Check-in

States that want to issue a Real ID card that uses the FIPS 201 standard would need to incorporate smart card technology into the card. However, the states would not necessarily have to deploy any significant new infrastructure to use the smart card features. Each state individually could decide whether and how to use the personal identity verification applications in situations unrelated to Federal use.

Examples of how state divisions of motor vehicles (DMVs) and law enforcement agencies could use and benefit from the use of smart cards are listed below. These and other applications could be phased in over time as the opportunity and economics of the applications evolve for each state.

- Driver's license renewal. Renewal of driver's licenses could be expedited by an applicant coming to a DMV office or kiosk, inserting the smart card and getting a new card automatically.

- Driving privileges. A DMV could revoke driving privileges for various infractions (for example, DUI, tickets) and still allow the individual to use the card for identification purposes.

- Ticketing. Law enforcement officers could issue tickets by reading the smart card chip and getting all driver demographic data from the card automatically.

- Driver histories. Driver history could be kept on the card enabling improved safety on highways where access to backend systems may not be available.

The Benefits of Smart Card Technology

Unlike alternative, less secure ID card technologies (such as magnetic stripe, printed bar code, optical, or RFID), smart card technology supports numerous unique features that can strengthen the security and privacy of any ID system.

Strong Identity Authentication. One essential characteristic of a secure ID system is the ability to link the individual possessing an identity document securely to the document, thus providing strong authentication of the individual’s identity. Smart card technology supports PINs, biometric factors, and visual identity verification. For example, the REAL ID Act requires that each person applying for a driver’s license or identification card be subjected to a facial image capture. This facial biometric factor can be stored directly in the secure chip in the smart card and used to verify that the individual presenting the card is the individual to whom the card was issued.

If states want to implement other biometric factors (for example, fingerprints), the biometric that is captured when the cardholder applies for the card (or is enrolled in the identification system) can be stored securely on the card. It can then be matched either on or off the card (in a reader or against a database) to verify the cardholder’s identity. In addition, states can establish databases to achieve the goal of “one credential, one record, and one identity.”

Strong Credential Security. Protecting the privacy, authenticity, and integrity of the data encoded on an ID is a primary requirement for a secure ID card. Smart cards support the encryption of sensitive data, both on the credential and during communications with an external reader. Digital signatures can be used to ensure data integrity and authenticate both the card and the credentials on the card, with multiple signatures required if different authorities create the data. To ensure privacy, applications and data must be designed to prevent information sharing.

Strong Card Security. When compared to other tamper-resistant ID cards, smart cards represent the best balance between security and cost. When used with technologies such as public key cryptography and biometrics, smart cards are almost impossible to duplicate or forge. Data stored in the chip cannot be modified without proper authorization (a password, biometric template, or cryptographic access key).

Smart cards also help deter counterfeiting and thwart tampering. Smart cards include a wide variety of hardware and software capabilities that can be used to detect and react to tampering attempts and counter possible attacks. When smart ID cards will also be used for manual identity verification, visual security features can be added to a smart card body.

Adding a smart card chip to a Real ID would exponentially increase the difficulty of making a fraudulent ID card. The vulnerabilities of printed plastic ID cards are well known-fake state IDs are readily available for purchase over the Internet or in rogue ID card facilities. Smart cards deter forgers and can ensure that only the person to whom the card is issued will be able to verify themselves when the card is presented. No other technology can offer such secure, trusted, and cost-effective identification capabilities.

* Strong Support for Privacy.* The use of smart cards strengthens the ability of a system to protect individual privacy. Unlike other identification technologies, smart cards can implement a personal firewall for an individual’s data, releasing only the information required and only when it is required. The card’s unique ability to verify the authority of the information requestor and the card’s strong security at both the card and data level make smart cards an excellent guardian of a cardholder’s personal information. Unlike other forms of identification (such as a printed driver’s license), a smart card does not reveal all of an individual’s personal information (including potentially irrelevant information) when it is presented. Information embedded on the chip can be protected so that it cannot be surreptitiously scanned or skimmed, or otherwise obtained without the knowledge of the user. Personal information stored on the smart card can be accessed only through user-presented PINs and passwords or by biometric matches at the place of use. By allowing authorized, authenticated access to only the information required for a transaction, a smart card-based ID system can protect an individual's privacy while ensuring that the individual is properly identified.

Flexibility as a Secure Multi-Use Credential. The driver’s license is currently a multi-use credential. It not only indicates that the cardholder has driving privileges, it also serves as the default credential for establishing that the cardholder can board an aircraft, engage in age-related retail purchases, establish banking relationships, complete retail point-of-sale transactions, and apply for employment. Smart card technology can support these current uses along with any additional applications that enhance citizen convenience and/or government service efficiency. For example, smart cards provide the unique capability to easily combine identification and authentication in both the physical and digital worlds. This capability can generate significant savings for states. A smart card-based driver’s license or ID card could not only indicate privileges and allow physical access to services, it could also allow individuals to file taxes, request official papers (e.g., birth certificates) online, or access secure networks. Multiple applications (with their required data elements) can be stored securely on the smart ID card at issuance or added after the card is issued, allowing functionality to be added over the life of the driver’s license or ID card.

Standards-Based Technology. Smart card technology is based on mature international standards (ISO/IEC 7816 for contact smart cards and ISO/IEC 14443 for contactless smart cards). Cards complying with standards are developed commercially and have an established market presence. Multiple vendors can supply the standards-based components necessary to implement a smart card-based ID system, providing buyers with interoperable equipment and technology at competitive prices.

Cost-Effective and Flexible Offline Verification. In addition to the privacy and security benefits afforded by smart cards, the technology also delivers features that support cost-effective offline verification and efficient use of the ID card once the card has been issued.

Verification of a cardholder's identity is often required at multiple locations or at points that do not have online connections. A smart card-based ID system can be deployed cost-effectively at multiple locations by using small, secure, and low-cost portable readers that take advantage of the smart card’s ability to provide offline identity verification. For example, verifying a cardholder’s identity with biometrics would not require access to an online database: the smart card can securely hold the necessary biometric identifier, with the secure chip on the card comparing it to the live biometric. The credential on a card can be authenticated by a reader using digital signatures contained on the ID card, making it a trusted credential-online or off.

One key issue that has been raised by different states and by the American Association of Motor Vehicle Administrators (AAMVA) is the cost of smart card technology. While a smart ID card or driver’s license may cost a little more than a plastic card, the cost of the card itself is a small fraction of the total cost of implementing an identity system that complies with the REAL ID Act. When considering costs, it is important to understand the advantage of an ID that is strongly tied to the bearer and enforces citizen privacy. By incorporating smart card technology into a Real ID, states can place a portable security agent in the hands of the cardholder, ensuring that the state’s security policy is enforced and that only an authorized cardholder can be authenticated before specific identity information is released. Any additional costs associated with the technology are a small price to pay for such robust security. Moreover, the ability of smart card technology to support additional applications can generate both cost savings and potential new revenue sources. In addition, smart card technology is flexible. Unlike today’s printed plastic cards, smart cards can be updated and managed throughout the life of the card.

Conclusion

The Smart Card Alliance strongly recommends that smart card technology be adopted as the underlying infrastructure for state driver’s licenses issued to comply with the requirements of the REAL ID Act of 2005. Smart cards have been proven to be the most cost effective and secure identity authentication and verification technology. They are already widely used for secure identification in both the public and private sectors, are based on international standards, can provide all of the features required to meet the security requirements of the REAL ID Act, and can deliver strong privacy protection for the cardholder’s personal information. Once states have adopted smart card identification technology, they can then decide whether to use the trusted Real ID credential for other applications beyond the Federal points of use according to their needs, budgets, and timeframes. Failure to embrace smart card technology will undermine the fundamental goal of the REAL ID Act-ensuring that the Real ID is not fake and that it is being used by the intended bearer.

I've got a biometric ID card

By Tom Geoghegan

BBC News Online

Biometric testing of face, eye and fingerprints could soon be used on every resident of the UK to create compulsory identity cards. BBC News Online's Tom Geoghegan volunteered for a pilot scheme and looked, unblinking, into the future.

Your life on a chip....within minutes

|

As I was led up to the first floor of the UK Passport Office in London's Victoria, the butterflies I used to get at the dentist began to flutter.

But as it turned out, the photo booth we passed on the way would have provided a more invasive exercise.

The simple 15-minute process to get my own identity card simulates what probably lies ahead for everyone.

Biometric tests are likely to be introduced for all new driving licences and passports from 2007. They could become compulsory six years later.

Explaining the purpose of the six-month pilot schemes being held across the UK, the Home Office's Peter Wilson said: "This isn't a test of the technology - that's likely to change in the future as things move on - it's the process.

"We're looking for customer reactions and perceptions, and any particular difficulties."

I was greeted in a reception area for enrolment, which consisted of filling out a form with basic information about myself such as gender, age, postcode and ethnic background.

Then I gave the form and my name to operator Rachel Davies, who fed the information into a computer.

I was ushered into a room and directed to sit in a sophisticated-looking booth, facing a hi-tech camera. No going back now.

The first test is the facial recognition, which is like a prolonged photograph without the flash.

Big Brother

No cheesy grins will be allowed, because the machine is scanning the measurements of your face and "doesn't like teeth".

|

BIOMETRIC PILOT SCHEMES

Target of 10,000 volunteers

No figures yet, but more than 16,000 have shown an interest

All details are destroyed and feedback anonymous

Set in London, Glasgow and Leicester, plus a mobile facility travelling the UK

Aims to identify any practical difficulties and give a cost projection of full scheme

Current cost predicted �1.3bn to �3.1bn

|

|

ID CARDS TIMETABLE

Nov 2003: Draft Bill published

Apr 2004: Pilot schemes begin

Autumn 2004: White Paper in Parliament

2005: Facial biometrics used on passports (scanned from passport photograph)

2007: New passports and driving licences to require biometrics, separate ID cards optional

2013: Parliament to vote on making it compulsory for all to have some form of biometric ID

|

The iris scan required more concentration because I had to stare hypnotically at two ellipses in the camera, while the machine verbally directed me.

"Come closer," says a Big Brother-like voice, instructing me to shuffle my seat forward while keeping my eyes fixed on the shapes.

After about 60 seconds, the machine indicated the scanning was complete.

No messy carbon required for the fingerprints. Instead I had to put each hand's four fingers, then the thumb, on a glass scanner.

My prints appeared on a computer screen and within minutes were compared against one million others which, for the sake of the pilot scheme, had been imported from the US.

With all three tests completed, I had to give a copy of my signature which they stored electronically.

I filled out a feedback form about my experience and then the card was ready and in my hands.

It's strange to think that the identity card's small microchip contains some personal information and my biometrics.

Although I don't feel psychologically invaded or like an android - as I feared I might - I can understand why others might.

Another simple fingerprint test verifies that I match the card and that's it, over.

If the government gets its way, the information on the chip would also be stored on a national identity register, accessible to the police, government departments, the Inland Revenue, immigration and intelligence services.

No wonder as I leave, a member of staff jokes: "We'll be tracking you."

RFID Chips To Travel in U.S. Passports

U.S. passports issued after October 2006 will contain embedded radio frequency identification chips that carry the holder's personal data and digital photo. Terrorism and ID theft fears drive most consumer objections.

By Laurie Sullivan

TechWeb News

State Department final regulations issued Tuesday said all U.S. passports issued after October 2006 will have embedded radio frequency identification chips that carry the holder's personal data and digital photo.

The department will begin the program in December 2005 with a pilot, issuing these passports to U.S. Government employees who use Official or Diplomatic passports for government travel. The International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), a United Nations agency, has developed international specifications for electronic passports meant to keep information such as name, nationality, sex, date of birth, place of birth and digitized photograph of the passport holder secure. United Kingdom and Germany also have announced similar plans.

The passports will have 64 kilobyte RFID chip to permit adequate storage room in case additional data, or fingerprints or iris scan biometric technology is added in the future. The United States will follow ICAO's international specifications to participate in a global electronic passport initiative. The specification indicates a data format and use of a Public Key Infrastructure (PKI) that permits digital signatures to protect the data from tampering, according to the Bush administration.

Consumer opposition for implanting RFID chips in passports has grown during the past year as fear that identity thieves could steal personal information embedded in the chip within the passport. The State Department this year received 2,335 comments on the project, and 98.5 percent were negative, mostly focusing on security and privacy concerns, and concerns about being identified by terrorists as a U.S. citizen.

Some comments called for the inclusion of an anti-skimming device that would block unauthorized connections with the readable chip to gain access to the data. "The doomsday scenario has been the ability for terrorist to drive by several caf�s to find and target the most Americans in one place," said Ray Everett-Church, attorney and principal consultant at PrivacyClue LLC. "I'm not sure how realistic that is, but when you work with these types of technologies you need to play out some of the possibilities to calm peoples' fears."

The State Department said it is planning to add technology, such as basic access control and anti-skimming material, to address fears related to skimming and eavesdropping. The anti-skimming material is being design into the front cover and spine of the electronic passport. The idea is to reduce the threat of skimming from distances beyond the ten centimeters, as long as the passport book is closed or nearly closed.

Germany To Issue Passports with Biometric Data This Fall

First passport in Europe to use RFID technology.

John Blau, IDG News Service June 02, 2005

DUSSELDORF, GERMANY -- Germany has taken a big step in the battle against organized crime and terrorism by unveiling a new passport with a chip that contains biometric data. The country plans to be among the first in Europe to issue biometric passes, starting Nov. 1.

Otto Schily presented the German biometric passport at a ceremony in Berlin on yesterday, the Interior Ministry said in a statement.

The new passport, valid for 10 years, will include an embedded RFID (radio frequency identification chip) that will initially store a digital photo of the passport holder's face. Starting in March 2007, the holder's left and right index fingerprints will also be stored on the chip.

The reasons for using noncontact RFID chips are twofold: contact points in traditional chip cards are not designed for 10 years of use; and passports don't fit in present chip-card readers, according to Germany's Federal Office for Information Security (BSI).

Readers Ready

Germany's new biometric passports are based on specifications approved in May by the New Technologies Working Group of the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO).

At this year's CeBIT trade show in March in Hanover, Germany, BSI presented the first ICAO-compliant reader for the new passports. The RFID chip can only be read by certified reading devices.

The European Union has asked for an extension of the Oct. 26 deadline imposed by Washington to implement new U.S. rules on issuing biometric passports. Washington is demanding that all passports issued by Australia, Japan, and E.U. member states after this deadline have biometric security elements for holders to enjoy visa-free U.S. visits of up to 90 days.

Some critics warn that the chips could be scanned remotely, but Schily said this is not possible with the German version, which can only be scanned when the passport is open and the reading device has calculated a special access code.

EU readies bio-passports

Reuters, The Associated Press

Published: June 29, 2006

BRUSSELS EU governments should be ready to issue new biometric passports containing facial images by Aug. 28 at the latest, the Union's justice and home affairs commissioner, Franco Frattini, said Thursday.

European citizens without the new passports would probably still be able to travel to the United States without visas after the August deadline, Frattini said at a news conference here. He said he was confident that the United States could be persuaded to extend the deadline for the use of biometric passports.

"I am not so sure about the final positive result but I can just anticipate - I am quite confident - that probably the United States will give Europeans some further delay," he said.

Frattini made the remarks despite what he called a "very rigid interpretation" by Congress that passengers without biometric passports would need individual visas after August, even if they came from visa-waiver countries.

The United States requires no visas for citizens of 15 of the 25 EU states, but the U.S. visa-waiver program does not apply to Greece or nine new, mostly ex- communist, member states.

To meet the new requirements, passports issued by EU member states after Aug. 28 are required to have digital photographs stored in a microchip embedded in the document.

At the news briefing, Frattini announced a further requirement for new passports issued after June 28, 2009, to store two fingerprints of their holders on the passport chip.

"We have to be very clear that no violation of privacy of individuals can be allowed," he added. "This is a key step forward to render passports of EU citizens more secure and reliable."

Officials said most EU governments will meet the August deadline, with Italy and Germany, among others, expected to start issuing the new passports later in the year. Member states have had since February 2005 to get ready to add the chip with facial scans to their passports.

EU officials said the biometric features, which reduce patterns of fingerprints, faces and irises to mathematical algorithms stored on a chip, would go beyond security standards demanded by the United States.

Here's two examples of Smart Card Companies with links provided

IDenticard Established in 1970 and with corporate offices in Lancaster, PA (USA), IDenticard� is recognized as a leading producer of biometric security identification and access control systems. The company provides a flexible line of fully integrated products and systems -- including complete sophisticated digital imaging and access control systems, custom-designed laminated, PVC, and smart cards, laminators, ID card printers, cameras, and bar code and biometric readers. All IDenticard system solutions can be easily upgraded to meet the growing security demands of customers.

Smart Card

ACS Founded in 1995 and now listed in the Hong Kong Stock Exchange, Advanced Card Systems Holdings Limited (ACS) is one of the selected groups of global companies at the forefront of the smart card revolution. ACS develops, manufactures, and distributes a wide range of high quality smart card reading/writing devices, smart cards, and related products to over 80 countries worldwide, facilitating an easier adoption of smart card applications in different industries.

As the one of the world's leading supplier of PC-linked smart card readers, ACS has the technology, expertise, and global resources to develop and offer the next generation in smart card versatility to satisfy the needs of its customers worldwide.

Smart Card Reader

|